Women and Lung Cancer: Gender Equality at a Crossroad?.

EVER SINCE THE AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY BEGAN REporting incidence and mortality data on specific cancers, lung cancer has stood out as a predominantly male disease. However, since World War II, when cigarette smoking became socially acceptable for and marketed to women, their lung cancer incidence rates have risen. Gender equality in lung cancer incidence rates may be attained in the near future.

Until recently, women had lower incidence of and mortality rates from lung cancer than men, either because women did not smoke or started smoking at a later age than men. Male and female smokers differ in the histological types of lung cancer with which they are diagnosed; women are more likely than men to develop adenocarcinoma. This difference in histology has been attributed to differences in the tar content of the cigarettes men and women smoke and in their mode of inhalation.

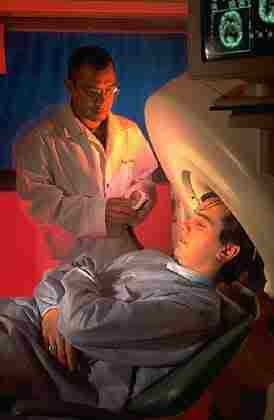

The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators address 2 interesting questions regarding women, men, cigarettes, and lung cancer. The current study explores gender differences in both lung cancer risk and lung cancer survival in the context of a low-dose spiral computed tomographic screening program in which all participants were cigarette smokers. In a cohort of screenees, women were found to have a higher lung cancer risk than men. This prospective cohort study is the first in which such a gender difference has been observed, but the cohort differs from others in its selection factors. Screenees had to be older than 40 years and to have a smoking history; they were also volunteers for an expensive experimental screening procedure not covered by insurance. Screen-detected cancers are known to differ from symptom-detected cancers. The findings of this important study with regard to female susceptibility are provocative, but such an analysis in the context of a screening study raises concerns about overdiagnosis bias; ie, a significant excess of lung cancers may be diagnosed in which unknown gender differences may play a role.

The study by these investigators also found that women had better survival than men. Their findings demonstrate that screening behavior does not account for the gender difference in survival; among men and women who were selected by the same criteria and screened with equal vigor, the survival rates were still better among women than men.

As the authors describe in their article, a series of case-control studies, starting with one by Risch et al, have found a somewhat higher risk of lung cancer in female smokers than in male smokers at comparable pack-years of smoking. Most other case-control studies that have explored this issue have concurred, with notable exceptions; the cohort studies have consistently not shown an excess risk for women under the same circumstances. When observational studies present a new finding, possible biological explanations for the finding quickly proliferate. The explanations for gender differences in lung cancer include reproductive and hormonal factors and differences in cytochrome P-450 enzymes with concomitant differences in DNA adduct levels between female and male smokers. However, the conflicting results of case-control and cohort studies are more likely to be due to methodological differences; biases, such as recall bias; computation of rate ratios as opposed to odds ratios (ORs); or confounders in the measurement of smoking exposure for men and women. Risch and Miller have suggested that, although among smokers women may have higher risks of developing lung cancer than men, among nonsmokers women may have lower risks, leading to a lower overall female:male risk ratio. However, relatively few nonsmokers develop lung cancer, and the hypothesized interaction between gender and smoking status is unlikely to account for the differences in results between the 2 study designs.

Can a gender difference be observed in other tobacco-related cancers? In a population-based case-control study of pancreatic cancer in Canada, Howe et al observed increased female susceptibility to pancreatic cancer among smokers. However, most other studies, both case-control and cohort, have not found gender differences in risk factors for pancreatic cancer. A recent case-control study of risk of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma found an OR of 1.8 for women compared with men who had similar cigarette smoking exposure levels. However, a pooled analysis of 14 case-control studies found no difference in risk of bladder cancer between male and female smokers.

The association between gender and lung cancer survival has been better documented than that between gender and incidence. Among patients with lung cancer, under a variety of circumstances, women have consistently been found to have better survival than men. These have included those with resectable or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer, other histological types of lung cancer, and studies in single institutions or with administrative databases. Vollset et al recently found that compared with men diagnosed at the same age and smoking the same number of cigarettes per day, women lived longer. This pattern has been observed not only among patients with lung cancer, but also among those with other causes of smoking-related mortality, including cardiovascular disease.

The reasons women live with lung cancer longer than men are unclear. Among nonsmokers, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is diagnosed more often in women than in men and appears to be more responsive to certain agents, such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors gefitinib and erlotinib, in women than in men. Do women fare better because of their body size, better health behaviors, hormonal and reproductive factors, different cigarette smoking histories or patterns, or other factors? Women's stage-for-stage advantage in survival appears to be a host effect and applies to all the major histological types of lung cancer. The biological differences in lung carcinogenesis between men and women, and their differences in responsiveness to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors for bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and certain subsets of adenocarcinoma, suggest that tumor biology also plays a key role. An effort to understand the tumor and host factors that underlie the female survival advantage in lung cancer could potentially yield major benefits for the treatment of both sexes.

The prototypical male smoker, the now infamous “Marlboro Man,” no longer represents the cigarette smoking population. In any event, he presumably died of lung cancer. The once prevalent adage, “You've come a long way, Baby!” geared to female smokers, unfortunately now applies to increased smoking prevalence and lung cancer risk among women. To prevent gender equality in lung cancer from becoming a reality, it's now time for women to turn back.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home