Women's Susceptibility to Tobacco Carcinogens and Survival After Diagnosis of Lung Cancer.

IN 2006 IN THE UNITED STATES, IT is estimated that lung cancer will cause 73 020 deaths in women, proportionately only slightly fewer than the estimated 90 470 deaths in men. 1 Lung cancer now accounts for more deaths in women than any other cancer, more even than the second and third cancer killers (breast and colon cancer) combined.

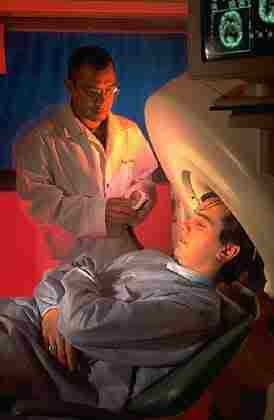

Research to quantify the benefit of computed tomographic (CT) screening for lung cancer in preventing deaths is ongoing. We previously reported on the Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP) baseline screening study of 2490 high-risk persons, which indicated that women have a higher absolute risk for lung cancer than do men of the same age with the same history of smoking. There have been other studies indicating that women have a higher relative risk of getting lung cancer than men; other studies disagree, the issue being the smoker vs nonsmoker risk ratio.

Sex differences in rates of survival following diagnosis of lung cancer have also been reported. Women have been reported to have higher survival rates regardless of the stage of the disease at diagnosis, the most recent evidence in the United States derived from the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and a large cohort at the Mayo Clinic.

Since our previous report, screening has continued at the original ELCAP institutions and has markedly expanded the amount of poolable data by institutions collaborating worldwide in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Project (I-ELCAP). In this article, we again address the lung cancer risk of women compared with men, accounting for age and history of smoking, but herein we also compare the rate of fatal outcomes between sexes.

COMMENT

Following up on our previous study, the findings reported herein again indicate that the risk of lung cancer is higher in women who smoke than in men of the same age who smoke the same amount.

The diagnoses were initially derived in the institutions in which the screenees were cared for, but in 222 of the 269 cases, the pathology specimens were independently reviewed by an expert panel of pulmonary pathologists. This panel confirmed all of the 222 cases as representing lung cancer, changing only the cell-type particulars in some of them. The low proportions of squamous and small cell carcinomas among the diagnosed cases were to be expected, as baseline screening less commonly leads to the detection of relatively fast-growing types, and also because there has been a shift to adenocarcinoma in cancer registry data in the United States and elsewhere.

The results of our analysis do involve some residual confounding by age and/or smoking, despite the data, but this confounding is negative, resulting in a diluted association. As for potential confounding by other airborne carcinogens, the exposures presumably are more common and more pronounced among men, with the consequent bias again diluting rather than accentuating the apparent role of sex.

Our results also raise other questions. First, could the pursuit of malignancy diagnosis have been more vigorous with women screenees? We see no reason to presume this: not only was the diagnostic protocol the same for the 2 sexes, but its recommendations were followed equally. Had the reading of the images been biased in favor of more common nodule detection in the women, this would have accentuated the frequency of relatively small tumors among the diagnosed cases in the women (being that relatively small nodules are less readily detectable), but the proportions of tumors under 10 mm in diameter were quite similar for women and men (0.11 [17/156] vs 0.09 [10/113], respectively).

Second, could women more commonly have presented themselves for screening on the prompting not merely of risk, but also the presence of cancer-suggestive symptoms? Again, we see no reason to presume this. Nevertheless, if this was the case, the largest tumors would have been relatively more common in the cases diagnosed in the women (as larger cancers are more likely to be symptomatic). But the proportion of tumors more than 20 mm in diameter was actually lower in the women than in the men (0.23 [36/156] vs 0.30 [34/113], respectively). Thus, insofar as some of the diagnosed cases actually were symptomatic and differentially so between the sexes, this again more likely diluted rather than accentuated the apparent role of patient sex.

Third, could the higher prevalence of detected cancer in women have resulted from a generally lesser aggressiveness—lower rate of growth—of the women's cancers compared with those of the men? We note that for the slowest-growing malignancies, typical carcinoids and adenocarcinomas of the bronchioloalveolar subtype, the proportions in women's and men's cases were 6% (9/156) and 4% (5/113), respectively. Also, for the fastest-growing type, small cell carcinoma, the corresponding proportions were 3% (4/156) and 11% (12/113), respectively. The degree of aggressiveness of the women's cancers thus tended to be slightly lower than that of the men's. But if in 10% of the women's cases the growth rate was, for example, one half of that in the men's cases, this would have made the prevalence OR (incidence density) no higher than 1.1. Insofar as a given level of smoking causes lung cancer more commonly in women than in men, the excess cases are principally adenocarcinomas, as has been shown in other studies.

The hypothesis that women may be more susceptible to tobacco carcinogens is biologically plausible. While evidence from some epidemiological cohort studies does not substantiate this idea, a subsequent study based on the national SEER registry again suggested the increased susceptibility of women. If additional studies add supporting evidence, the notion of women's susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens warrants serious consideration.

If lung cancer risk for women who smoke is indeed higher than the risk for men of the same age who smoke, as indicated by the evidence presented here, this suggests that antismoking efforts directed toward girls and women need to be even more serious than those directed toward boys and men. In the same vein, insofar as screening for lung cancer is practiced among smokers, female sex calls for screening at lower levels of smoking history than the corresponding indication threshold in men. Specifically, if men of a given age are to be screened if the number of pack-years of past smoking is at least X, the regression analysis of the 2 screening series combined suggests that the corresponding threshold for women would be X-0.662/0.0138 = X-48 pack-years, where 0.662 and 0.0138 are the fitted coefficients of the indicator of female sex and pack-years of smoking; that is, that the screening threshold for women of a given age should be 50 pack-years lower than that for men of the same age.

It is well-established by the evidence accumulated over the past 20 years that women with lung cancer survive the disease better than men, and that this difference is more pronounced when the cancer is diagnosed at an early stage. Cancer stage at diagnosis, cell type, or treatment do not appear to be entirely explanatory of this difference. As 85% (229/269) of the cases considered here were clinical stage I at diagnosis, the fatality hazard ratio in favor of women, conditional for pack-years of smoking, disease stage, tumor cell type, and resection was more pronounced than those reported by others. Despite the conditionality, it is not clear whether this survival difference is because lung cancer in women tends to be more commonly curable or less malignant. If lung cancer is more commonly curable in women, then the need to screen women at a lower threshold than men is warranted. If lung cancer is less malignant in women, there may be less need to screen women at a lower threshold.

Conclusion:

Women appear to have increased susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens but have a lower rate of fatal outcome of lung cancer compared with men.

2 Comments:

Cool site! Welcome to my sites too:

replicas louis vuitton

cash advance payday paycheck

application loan payday quick

loan personal quick

approval home loan quick

payday paycheck loan

advance cash loan loan online payday payday

fast easy payday loan

emergency loan payday

24 hour payday loan

free credit report and score

See you later, thanks

Excellent job, man. Bookmark!

herbs weight loss

fast weight loss diet program burn fat lose weight

Bye!

Post a Comment

<< Home