Reclaiming Wellness-Living With Bodily Problems, As Narrated by Men With Advanced Prostate Cancer.

We are usually unaware of our body, taking it for granted until illness and pain rise our awareness. Our body, however, is not separated from our person as in the Cartesian split, but is embodied as our experience of the lived body. Our body's call for attention, for example, in the form of fatigue signaling the probable presence of disease, is often the first indication of cancer. Such calls for attention are generally labeled "symptoms." However, the significance an ill person gives to a symptom is influenced not only by its frequency or the distress it causes but also by its meaning.

More recent concepts such as "symptom distress" (ie, discomfort caused by symptoms) and "symptom experience" (ie, symptom occurrence and the distress it causes) have broadened our view. The term "symptom," however, remains problematic because it is connected to the biomedical relationship to "the body." The assumption is that the symptom can be defined and managed beyond the person by healthcare professionals, without including the person's own narrative and personal meanings in the therapeutic process. Thus, a more meaning-centered approach using the terms problems and/or needs has been suggested. These terms imply something that is difficult to deal with and understand and, more importantly, that the power to act remains with the person experiencing the problem. For this reason, we use the term "problems," and in the present article, we focus on "bodily problems" as described by our participants.

Living with advanced cancer is related to living with considerable bodily problems. Prostate cancer (PC) is the most frequent form of male cancer in Sweden, with more than 9,000 men diagnosed with PC in 2003, the majority over 70 years old. The highest incidence rates of PC are found in North America and Scandinavia, and the lowest in China and parts of Asia. Prostate cancer can be divided into 4 stages: disease localized to the prostate gland; locally advanced disease; primary metastatic disease; and hormone refractory PC (HRPC), which manifests with or without skeletal metastases.

The primary treatment of metastatic PC is to remove (block) the production of testicular androgen by surgical or medical castration. Castration has a number of side effects, such as loss of libido, impotence, hot flushes, anemia, hair loss, osteoporosis, fatigue, and psychological factors. Nausea, vomiting, breast tenderness, and breast enlargement also occur.

Even if metastatic PC is successfully treated with androgen ablation, the response to treatment is temporary and after 1 to 4 years, depending on disease stage, castration is no longer effective and the disease progresses. The first sign of progression, indicating that some PC cells are proliferating despite lack of androgens, is an increase in prostate-specific antigen, the widely used serum tumor marker for PC, and the disease is then classified as "HRPC." The main problem in patients with HRPC is pain caused by skeletal metastases and complications such as pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, anemia, and thrombocytopenia with a major decrease in performance status. Other bodily problems associated with HRPC are fatigue, anorexia, lymphedema, urinary obstruction, hematuria, incontinence, and rectal obstruction. The median survival time with increasing prostate-specific antigen values and skeletal metastases varies considerably, ranging from 10 to 52 weeks.

A literature search revealed only a few studies that illuminated living with advanced PC from the men's perspective, and these were performed in mixed groups of men in different stages of disease or treatment, in order to study marital relations and communication, treatment decisions, and quality of care. Studies on symptoms, or bodily problems, focused mainly on sexual functioning. However, Clark et al interviewed men treated for metastatic PC with castration and found that the men's experiences ranged from not being at all worried to being very distressed by bodily changes such as loss of muscle tone, weight gain, breast enlargement, loss of body hair, and hot flushes. Jakobsson et al, studying men with PC at different disease stages, found that they experienced a changed life continuum as a result of physical and existential fatigue, pain, micturition problems, and an altered sex life. Having problems urinating and presence of an indwelling catheter and the consequences for sexual life radically affect the men's autonomy and quality of life, and, consequently, their life continuum. Harden et al and Chapple and Ziebland interviewed men at different stages of PC and found that losing urinary control and experiencing sexual dysfunction, hormonal alterations, and fatigue were their main problems.

Hormonal treatment in particular had extensive consequences and affected some men's sense of masculinity. Navon and Morag have conducted interviews with men with PC about ways of coping with hormonal treatment. Their findings present a fairly gloomy picture of life during hormonal treatment. The interviewees' chief psychosocial problems were feminization of their bodies, sexual dysfunction, and disrupted intimacy with their partner. Because of castration, participants with PC receiving hormonal therapy found themselves in a liminal state of unclassifiability as men.

Although there is quite an extensive literature of quantitative studies on the side effects of treatment and symptoms in PC, relatively little is known about sense of embodiment experienced by those affected. A review of the literature shows that studies often have participants at different stages of PC, and that a meaning-centered approach to bodily symptoms or problems other than those affecting sexuality and those due to hormonal treatment is lacking, especially in relation to men with skeletal metastases for whom hormonal treatment is no longer effective.

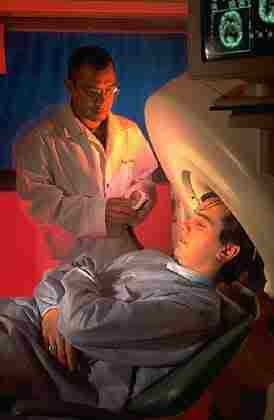

Having advanced prostate cancer means living with considerable bodily problems, a living we know little about. Thus, the aim of this study was to illuminate meanings of living with bodily problems, as narrated by men with advanced metastasized hormone refractory prostate cancer. Eighteen participants were interviewed, and the text was analyzed using a phenomenological-hermeneutic approach. Findings show that meanings of living with bodily problems are to live in cyclical movements between experiencing wellness and experiencing illness. New, or changed, bodily problems mean losing wellness and experiences of being ill. Understanding and, to some extent, being in control of bodily problems, make it possible to reclaim wellness and to experience oneself as being well.

Findings also show that pain and fatigue are the most prominent problems and that they have different meanings. Pain being a threat of dying in agony, whereas fatigue is more of an emissary of death. Reclaiming wellness versus adaptation and enduring versus suffering deriving from 2 different perspectives, the inside or life world perspective and the outside or professional perspective, are questions discussed in the article. One clinical implication for nursing is the risk of obstructing the patients' possibility of reclaiming wellness by focusing on symptoms and disease.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home